Art is not only the product of human talent, but also appears to be in some ways the product of scientific and technological innovations. According to the Oxford dictionary, “art is the expression or application of human creative skill and imagination, typically in a visual form such as painting or sculpture, producing works to be appreciated primarily for their beauty or emotional power.” Art can be seen as a process, a practice and a product of cultural knowledge. Through my research, I have noticed that turning points in the history of occidental art coincide with periods of major scientific and technological innovations. To enlighten the effects of science and technology on art, I have chosen to focus on three periods: The Renaissance, period of transition between the “darkness” of the Middle Ages and the modern period, the late 19th century characterized by radical changes in painting (Impressionism, abstraction). Finally, I will study the impact of internet and the digital era on art, concentrating mainly on painting, and casting aside many fascinating genres such as sculpture and installation art.

The cultural, scientific and technological revolution that took place in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries, led to major transformations in art: transformation of status (from religious to secular), topics (antique and human centred), forms of representations and diffusion.

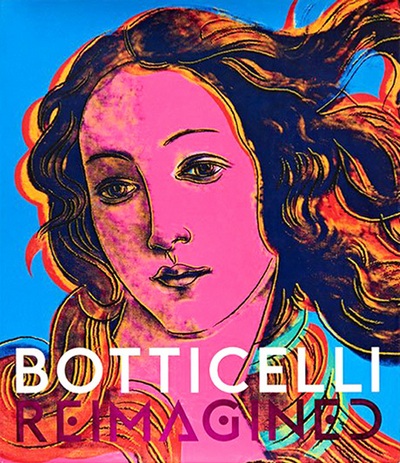

In 1454, Johannes Gutenberg (1398-1468) used for the first time the printing press, a technique he had taken from China and perfected. It affected art greatly. Printed books gave to artists an access to forgotten antique knowledge and new sources of inspiration. Painters, sculptors and architects would use Greek and roman mythology episodes as new themes for their work. Moreover, art stopped to be a monopoly of the religious monks and artists started to come from different social backgrounds. The growing amount of artists led to a flourishing number of paintings inspired by new subjects. Botticelli’s (1445-1510) Birth of Venus (1486) is a perfect example of the time’s changes. It is a non-religious painting, produced by a non-clerical artist. The printing press also led to the diffusion of woodcut, an ancient technique that was used to illustrate the incunabula and that rapidly replaced illuminations which were a long and costly process. Artistic images even became the main topics of books such as The Apocalypse by Albrecht Dürer (1471-1528), which was a novelty. Not only did the newly printing press opened accesses to art, it also transformed the status and the topics of artistic productions.

At the same period, the discovery of linear perspective by Brunelleschi (1377-1446) revolutionized the lines of representation. Artists became able to represent spaces in a very methodical way, perceiving the world as a sequence of geometrical forms that they could reproduce, following particular formulas. The first example of perfect perspective is Masaccio’s Holy Trinity, with the Virgin and Saint John and donors (1427-1428). Masaccio represented the characters in a realistic environment, giving to the viewer the impression of seeing the continuity of the room. It is the first painting in which all the characters (the saints and the donors) are the same size, which brings up its realism. The fact that the artist here paints everyone at the same scale shows the impact of perspective on him, which induced search for realism.

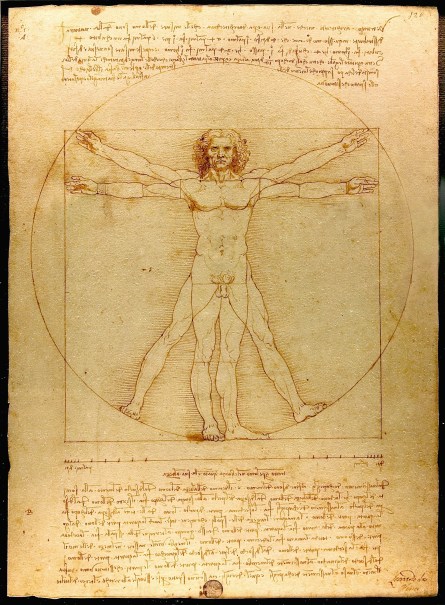

Lines of representation were also affected by another scientific discovery: Anatomy. In 1543, Andreas Vesalius (1514-1564), the first man to properly dissect a corpse, published his works on the human anatomy. This will revolutionize the representation of human bodies. Leonardo da Vinci (1452-1519), in his quest to achieve perfect proportions, “dissected more than ten human bodies, destroying all the various members and removing the minutest particles of the flesh”, which led him to produce his famous mathematical drawing of the Vitruvian man (1490). In Andrea Mantegna’s Saint Sebastian (1480), the depiction of the saint’s musculature and body proportions are central. Their preeminent aspect demonstrates the impact of these scientific discoveries on the artist and his knowledge of antique art.

The technological and scientific discoveries of the Renaissance gave artists tools and knowledge to represent the world as they saw it.

Another radical alteration of art, linked to scientific and technological discoveries, took place in the nineteenth century.

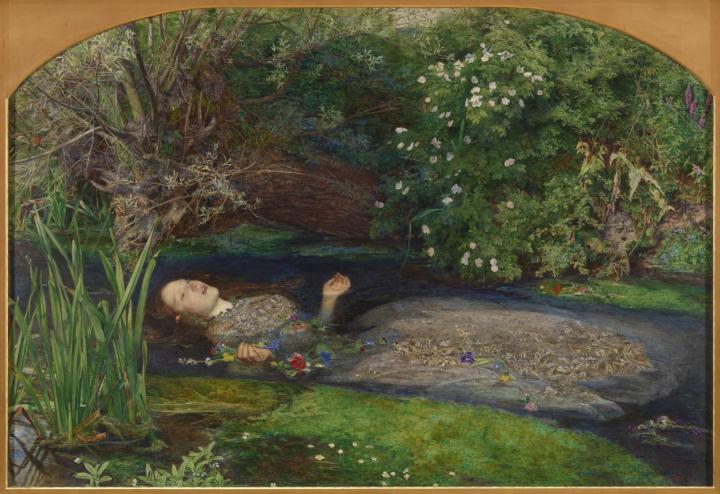

The invention of the tube of paint in 1841 by John Goffe Rand (1801-1873), perfected in 1859 by Alexandre Lefranc changed the practice of art. “Non-toxic colours” and ready-made art supplies modified the practice of oil painting but also that of watercolour. Before the end of the eighteenth century, watercolours were not perceived as a medium of their own, and therefore it had no vocabulary of its own. Thanks to the invention of iron tubes, watercolourists gained popularity as quoted in Graham Reynolds’(1914-2013) concise History of Watercolours: “this medium, willingly left in France to girl’s boarding schools, is used by British artists of the first rank”. Tube paints were also easy to carry. It enabled artists to paint outside, on the spot, and represent nature as they saw it. The Pre-Raphaelite’s motto “truth to nature” gives a very good idea of this opening to nature. In Millais’ (1829-1896) painting Ophelia (1851-1852) for instance, nature is depicted in a very realistic, almost photographic manner.

The photographic process (invented by Nicephorus Niepce in the 1820s) so deeply affected art that some painters saw in this technological invention the end of painting: “from this day on, painting is dead” (Paul Delaroche, 1839). Optical discoveries had been of some interest for painters since the beginning of the seventeenth century but none of them had ever been a threat to the essence of painting. Photographic process acted as a bomb. It greatly modified the hierarchy and nature of subjects and expression, as photography was a far better process to produce portraits and historical scenes by example. Affected by the realism of photography, “a plagiarism of nature through a lense” (Lamartine), artists felt the need to escape reality and duplication. This new quest led to the apparition of various artistic movements such as Impressionism and new concept such as abstraction. Like on photographs, impressionism put light at the chore of the canvas but in an attempt to express impressions rather than objective reality. At the very beginning of 20th century, the photographic process started to be recognised as a form of art in itself. Photographs have also been use, since the 1850’s, as a tool of diffusion, like printing press four centuries earlier.

The nineteenth century’s discoveries therefore led to a real democratization of the practice and the knowledge of art. They also radically altered the forms of expression and representation in art.

Art has been deeply affected by the recent digital revolution. The democratization process grew in the twentieth century thanks to the invention of the internet and digital technology.

Like the printing press in the 15th century, the internet is an amazing vector of massive diffusion leading to the democratization of art knowledge. Nowadays, people have a direct, free and immediate access to art. Art is now part of daily life; museums are not the only places of exhibition anymore, the domestic computer screen is also a space of display. Not only can internet be a way of learning about art (for artists and for amateurs), it is also used as a vector of communication by artists. Contemporary painters cannot exist, commercially speaking, without developing a website on which they exhibit their work. A wide range of applications like Instagram have been conceived to improve the quality of the images shown. And it has become possible to get a better view of a painting on a screen than hanged on a wall… This technological revolution deeply affected the perception of art. Art is at hand reach for who is interested. Art is everywhere.

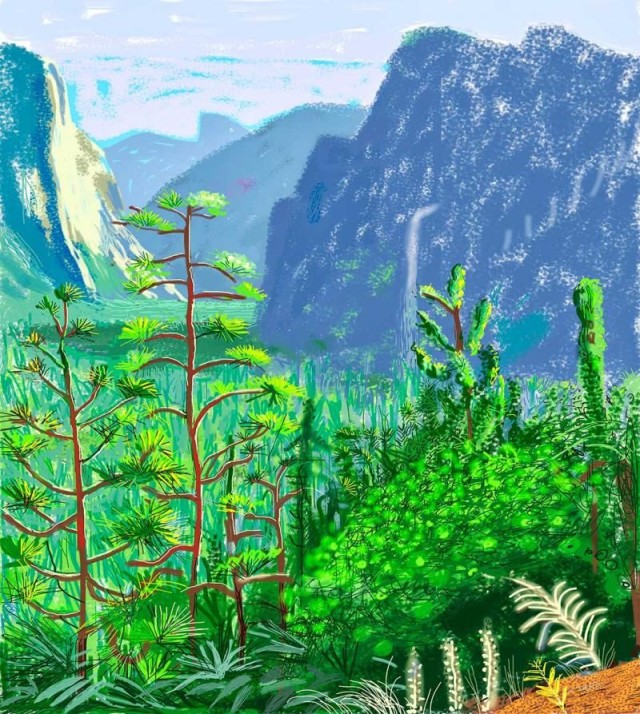

The era of digital technology adds a new dimension to art and questions its foundations in the meantime. Thanks to the apparition of smartphones and tablets as mediums and applications like “Brushes”, the digital painting is born. David Hockney has destabilized his public with his surprising series of “Yosemite landscapes” on iPad. The ability to duplicate, modify, transform images easily through processes like Photoshop, questions the singularity of those works of art, singularity that has always been prevailing so far. The exhibition Botticelli revisited at the Victoria and Albert museum, displayed artworks inspired by Botticelli’s art. There, seeing Botticelli’s works as art was a given. However, the more modern paintings’ artistic value is more questionable.

The technological discoveries of the 20th and the 21st centuries, did not just change the way artists paint, it also deeply blurred the limit between what is art and what is not. Paintings nowadays expand the limits of art, and contemporary artists often lead the viewer to redefine what is art.

Science and technology affected art in a numerous amount of ways. Not only did they change and improve the techniques used, they also contributed to alter radically the status, forms, topics and definition of art. Thanks to the discovery of the printing press, the invention of photography and the explosion of internet, artists and amateurs gained easy access to art, whether art is regarded as a practice or as an essential knowledge to keep on creating. The invention of perspective, the scientific observation of human bodies, the invention of the paint tube and the digital era encouraged (and at some point obliged) artists to look for new ways of representing their world. However, it is obvious that science and technology are not the only factors of transformation in art, and much is given to the human talent. One may wonder what other factors impacted art through its history?

VB