Simonetta Cattaneo was born I Genoa in 1453. In 1469, aged 16, she met Marco Vespucci, a distant cousin of the world-known cartographer Amerigo Vespucci. They married the same year which led Simonetta to move to Florence. There she found great success, particularly under the reign of Lorenzo de Medici (The Great). She was the admired by all artists and poets and loved by numerous men. Poliziano said himself:

She had the sweetest and most attractive manner so that all those who enjoyed the privilege of her friendship thought themselves beloved by her, and it seemed almost impossible that so many men would love her without exciting any jealousy, and so many women praise her without feeling any sense of envy.

Amongst her numerous suitors was Giuliano de Medici, Lorenzo’s brother. He enrolled himself in La Giostra (a jousting tournament) in 1475, and after winning it, crowned Simonetta Queen of Beauty. This is seen as the typical example of chivalrous courtly love in Florence at the time. While this episode has been described on numerous occasions it is not certain that Giuliano and Simonetta became lovers.

Sadly, la bella Simonetta’s fame was only short-lived. Her death in 1475 caused great sorrow amongst the Florentines. On the day of her burial, her body was carried through the streets of Florence, in a specially designed and ornate chariot. It was then placed in a chapel of the church of the Ognissanti, alongside other members of the Vespucci family, and later on Botticelli.

Although her life was short, she had a great impact on Florentine art in the early Renaissance. Most of the depictions of her known today were actually made after her death. While numerous legends surround her friendship with artists such as Botticelli, it is most probable that she only knew the painter Domenico Ghirlandaio, and the poet Poliziano.

Poliziano was the first to glorify Simonetta’s beauty, portraying her as the nymph in his book of poems Le Stanze. Her image gradually evolved from this and she was soon considered as the reincarnation of Dante’s Beatrice, and the living image of beauty. Amongst the other poets that described her were Naldo Naldi, Luca and Luigi Pulci, and even Lorenzo de Medici.

The most famous painter to have depicted her is Sandro Botticelli. He was said not have great interest in women, yet Simonetta Vespucci caught his attention. It was argued that she became the model for all his paintings. However, many scholars have argued that Botticelli’s works may have simply depicted the ideal woman according to poets and thinkers of the time. Indeed, while the portraits represent the specific features of Vespucci, their hair seems to possess god-like properties. Indeed, Botticelli gives it a true erotic power through the combination of alluring headdresses (never worn by respectable women) and untied hair (symbol of debauchery at the time). But the fact remains unclear.

It is therefore difficult to give a precise count of all the depictions of Vespucci. Even Pietro di Cosimo’s portrait of her seems to have been a fake. Some works however must be named.

First of all is Pallas subduing the Centaur, painted around 1482. This work was produced in honour of Giuliano de Medici, who died in 1478, and recalls the events of La Giostra. The metaphor of Pallas’s Victory over a centaur was chosen for two reasons. First of all, it is said to have been the scene depicted on the banner Giuliano was holding during the jute. Secondly, the centaur was a symbol of crime and folly. The work therefore symbolises the victory of the Medici over their enemies. The figure chosen for Pallas seems to be Simonetta Vespucci. According to many, this painting echoes the Primavera.

The Primavera on the other hand was a very enigmatic painting. Its true name is unknown to us today. It was only 70 years later, in Vasari’s Lives of the artists, that the idea of Primavera as a title appeared. From that day onwards it has been perceived as a celebration to spring. It presents figures in an orange grove. On the far left is Mercury dissipating the clouds of winter. Next to him are the three graces. In the centre is Venus, with cupid over her head. On the right Zephyrus is chasing a nymph named Chloris, while flora stands covered in flowers. While some argue that the painting illustrates Poliziano’s Stanze, others claim that it could be based on Ovid’s Metamorphosis or Lucretius’s De rerum natura. However, all agree that it combined the different elements of Sandro’s early works to create “one of the most radiant visions that has ever dawned on the heart of the poet-painter”. Simonetta Vespucci seems to have been the source of inspiration for many of the figures here: Flora, Venus or even one of the three graces. It is therefore seen by some as a way to honour her.

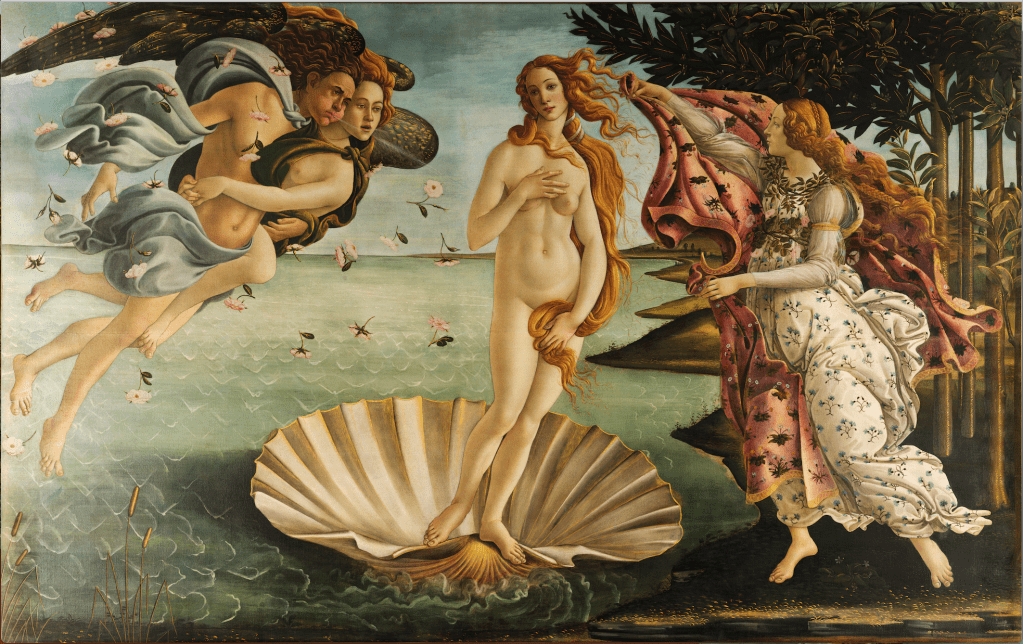

Primavera is almost always paired with The Birth of Venus, Botticelli’s most famous work. It depicts the myth of the birth of Venus (or Venus Anadyomene), child of the earth and the sea, and brought to shore in a shell. In the centre, Venus is presented rising from a scallop shell surrounded by by Zephyr, and what is commonly seen as Aura on the left, and one of the Hora of Spring. Again here the inspiration for the central figure seems to have been Vespucci. This leads certain scholars to interpret this painting both as a metaphor for the rebirth of the city of Florence, and an illustration the birth of Vespucci in Genoa in 1453.

Mars and Venus also clearly depicts Simonetta Vespucci. It presents the gods Mars sleeping under the gaze of Venus. Around them, four satyrs are playing with Mars’s war attributes. This work is often perceived as a marriage painting, placing it in a long lineage of works such as Titian’s Venus. Many objects can be read as indications to the god’s sexual relations. The context itself, a grove of myrtle, is traditionally associated with Venus and marriage. Some scholars also argue that this painting was also made in memory of Simonetta Vespucci. The wasp nest on the left of Mars’s ear could be seen as a reference to Vespucci herself (the wasp was a symbol of the Vespucci family).

Finally one can mention the Calumny of Apelles, one of Botticelli’s the less well-known paintings. This work is an allegory with nine figures personifying vices and virtues. The nude figure pointing upwards it Truth, in black is Repentance. Over the victim are in red and yellow Perfidy, and Calumny. Hooded and in black is Rancour obscuring King Midas’s view. Midas is surrounded with both Ignorance and Suspicion. Here Botticelli aims to recreate a painting by Apelles, recorded in an ekphrasis by Lucian. It is interesting here to see that several figures could be portraits of Vespucci: Truth and Perfidy, indicating that she would not necessarily be a symbol of virtue, but could be simply a model according to which Botticelli depicted most of his women.

However, looking at most of these paintings, it seems clear that Simonetta Vespucci was a symbol of virtue, grace and beauty. She takes part in a long lineage of women idealised in Florence, amongst which one can find Lucrezia Donati, Marietta degli Strozzi, Ginevra de Benci or Giovanna degli Albizi Tornabuoni. These Florentine women were the symbols of cultural revitalisation of late 15th century Florence. However, they were nothing more than muses for the artists, praised for their physical appearance. They were all beautiful and chaste, depicted either as nymphs or ideal brides, mothers and wives. Simonetta, however, stands out from her peers as she is said to have haunted literary and artistic Florence throughout the Renaissance.